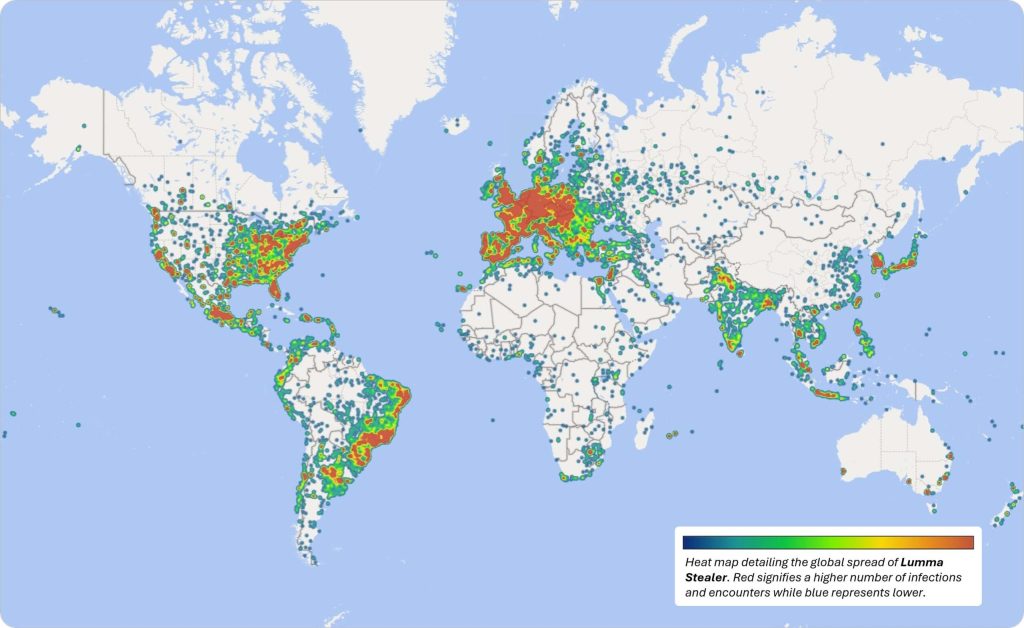

Microsoft recently disclosed a massive Lumma Stealer (aka LummaC2) campaign infecting Windows machines worldwide. In a coordinated action with the DOJ, Europol, and industry partners, Microsoft’s Digital Crimes Unit (DCU) disabled the Lumma infrastructure. Between March 16 and May 16, 2025, the company identified over 394,000 Windows PCs infected by Lumma. Authorities seized hundreds of command-and-control (C2) domains: Microsoft’s civil action took down ~2,300 malicious domains, and the U.S. DOJ obtained warrants to seize five user-panel sites. A Microsoft heatmap shows infections clustered globally (reds) across the Americas, Europe, and Asia. The DOJ noted that Lumma had been used in at least 1.7 million credential-theft incidents, targeting login data, banking and crypto accounts, and cryptocurrency seed phrases. Microsoft even alleges in court filings that Lumma “is the most widely distributed data-stealing malware family in the world”. In short, Lumma emerged as a rife infostealer, used in fraudulent bank transfers, crypto heists, and ransomware schemes worldwide.

What is Lumma Stealer?

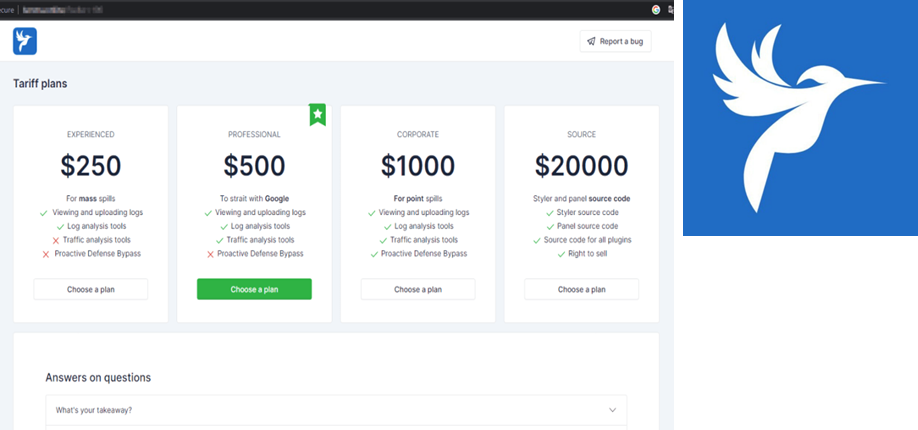

Lumma is a Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) info-stealer that has been advertised on underground forums since 2022. Its developer (alias “Shamel”) markets it via Telegram channels and dark-web sites. Customers pay for Lumma access and can generate custom malware builds through an online panel. Four service tiers have been documented (Experienced, Professional, Corporate, Source Code), ranging from roughly $250 up to $20,000 for full source access. Shamel reportedly had “about 400 active clients” as of late 2023. In effect, Lumma operates like a subscription service: buyers get a ready-made credential- and wallet-stealing payload, hosting infrastructure, and a dashboard to view stolen data.

Lumma’s purpose is straightforward: harvest sensitive data and monetize it. Microsoft notes it “monetize[s] stolen information or conduct[s] further exploitation”. Victims’ stolen credentials, cookies, crypto wallets, etc., can be sold or used for financial fraud. The malware is designed to be “easy to distribute, difficult to detect,” with built-in features to bypass security. Over successive versions, its author has hardened it against analysis and detection. In lab analysis, the Lumma binary was found to use extreme obfuscation (control-flow flattening, custom stack encryption, low-level syscalls and “Heavens Gate” 64-bit mode-switching) to thwart disassembly and debugging.

Microsoft tracks the main operator of Lumma (C2/infrastructure) as Storm-2477. Affiliates who pay Storm-2477 can launch their own Lumma campaigns. Many financially motivated gangs use it: for example, Microsoft observed ransomware-linked groups (e.g. “Octo Tempest”/Scattered Spider) deploying Lumma alongside other tools. In one March 2025 case, a Booking.com-themed phishing campaign (labeled “Storm-1865”) distributed Lumma to steal travel-industry credentials for fraud. Lumma has been reported in attacks on gaming, education, manufacturing, telecom, logistics, finance and healthcare sectors. In short, it became one of the most pervasive infostealers on the scene. By early 2025, some analysts noted it accounted for the majority of new infostealer incidents.

Infection Vectors & Delivery

Lumma spread through multi-channel campaigns using heavy social engineering. It never exploits a specific Windows vulnerability; instead it tricks users or abuses common services. Key distribution methods include:

- Phishing Emails: Malicious messages impersonate trusted brands and urge action. Microsoft saw campaigns spoofing Booking.com (sending fake review/invoice notices) and even niche services, with urgent subject lines. Victims are lured to click links or open attachments which ultimately deliver Lumma. One April 2025 campaign targeted Canadian businesses with “fitness plan” invoice lures; it led users through a traffic-direction system (Prometheus TDS) to a fake CAPTCHA page (ClickFix) that ran an mshta command. That in turn loaded Lumma (and even bundled the XWorm malware) via PowerShell.

- Malvertising / SEO Poisoning: Attackers injected fake ads into search results for common downloads (e.g. “Notepad++” or “Chrome update”). These ads pointed to cloned sites mimicking legitimate vendors, but the Download buttons delivered Lumma executables. In January 2025, security researchers found ~1,000 fake Reddit pages linking to fake WeTransfer downloads of Lumma. These sites all had credible-looking URLs (e.g. reddit…123.org) to fool victims into grabbing the stealer.

- Drive-by Downloads: Groups of legitimate websites were compromised and injected with malicious JavaScript. When users visited, the script would launch hidden payload downloads or display additional fake prompts. One documented case used a novel “EtherHiding” blockchain technique: compromised sites fetched malicious code from smart contracts on Binance Smart Chain, making it hard to block.

- Trojanized Software: Cracked or pirated app installers on file-sharing sites were bundled with Lumma. For example, fake VLC or ChatGPT apps contained no apparent payload on install, but silently ran Lumma after launch.

- Abuse of Repositories / Services: Public platforms are abused to cloak malware. Attackers have uploaded malicious ZIPs to GitHub, disguised as game cheats, cracked apps, or AI tools. Users who download these get a loader (“SmartLoader”) that drops Lumma Stealer. A recent Trend Micro analysis noted fake GitHub repos with AI-generated content pushed Lumma via this method. The ClickFix social-engineering trick became very common: fake CAPTCHA pages instruct victims to open Run and paste a malicious command (e.g. a PowerShell or mshta call) that downloads Lumma. This has been seen in hotel/phishing lures for months; even APT groups like APT28 and MuddyWater adopted ClickFix in late 2024.

- Other Malware Droppers: Some campaigns used one piece of malware to drop Lumma as a second-stage payload. For instance, Microsoft observed the DanaBot banking trojan delivering Lumma on infected PCs.

In all these methods, the payload is installed when the victim (often unwittingly) executes a command or installer. In one illustrative flow, clicking a fake Booking.com link led to a CAPTCHA page; following instructions copied a command that launched mshta.exe. That ran a JavaScript which invoked PowerShell to fetch and run the Lumma executable. In another, a multi-step script (via mshta, then JS, then PS) ultimately deployed Lumma and Xworm. These multi-stage chains allow Lumma to enter the system while trying to evade basic blocks.

Payload Execution & Obfuscation

Once delivered, Lumma executes as a native binary (written in C++/ASM) and immediately begins hiding. The loader typically spawns hidden processes or uses process hollowing: the malicious code injects itself into legitimate Windows processes (e.g. msbuild.exe, regasm.exe, regsvcs.exe, explorer.exe). By running inside trusted binaries, Lumma evades simple behavioral detection.

The Lumma executable is heavily obfuscated to resist analysis. Critical functions are wrapped in custom virtual machines, packed routines, and dead code. Microsoft’s malware analysts noted techniques like LLVM-based virtualization, control-flow flattening, stack encryption, and heavy use of direct system calls. These measures often break decompilers (e.g. IDA Pro) and make static analysis unreliable. In addition, nearly all C2 URLs and payload commands are encrypted in the binary (using ChaCha20 and custom algorithms) , so analysts must let it run to see its targets. In short, Lumma’s code tries to “blend in” by mimicking normal processes and by hiding its own logic behind layers of encryption and obfuscation.

Data Theft Capabilities

Lumma’s entire mission is data exfiltration. Its capabilities have grown with each version, but key targets include:

- Browser Data: It extracts saved passwords, session cookies, and autofill info from Chrome, Edge and other Chromium-based browsers, as well as Firefox/Gecko browsers.

- Credentials & Accounts: Lumma grabs login credentials for email, banking, and other services stored on the system.

- Crypto Wallets: The stealer searches for cryptocurrency wallet files and browser extensions. It specifically looks for wallets like MetaMask, Electrum, Exodus and associated key storage. Darktrace reported targets including Binance and Ethereum wallet files and even 2FA extensions like MetaMask and Authenticator.

- Other Apps: It copies configuration files or credentials from VPN clients (.ovpn), FTP clients, and chat apps like Telegram.

- User Documents: Lumma crawls user folders for documents and archives (especially .pdf, .docx, .rtf) and steals any it finds.

- System Metadata: To profile the victim, it logs system info – CPU model, OS version, language settings, installed apps, etc. .

Importantly, Lumma can also install additional payloads or plugins on the infected machine. Researchers observed that it often includes or fetches a clipboard-stealer plugin (which watches for copied cryptocurrency keys) and cryptocurrency miners. These extras may be dropped from C2 or bundled: for example, Microsoft saw a campaign where the downloaded executable contained both Lumma Stealer and the XWorm malware. The lumma panel supports “GET_MESSAGE” commands to fetch secondary payloads – in tests this returned empty arrays (no extra installs) except a few cases where the clipboard stealer and miner were provided.

All stolen data is sent back to the attackers via Lumma’s C2 network. The stealer uses encrypted HTTPS (often Cloudflare-proxied) to upload logs in chunks. Each stolen item is posted with a unique ID (the “SEND_MESSAGE” command in older versions) to the active C2 server. This robust C2 protocol allows very large amounts of data to be exfiltrated without alerting on a single huge upload.

Persistence & Evasion

While Lumma’s main focus is immediate data theft, it does implement persistence and anti-detection to prolong its presence. In practice, persistence may not be a top priority (some versions reportedly self-delete after stealing credentials), but emulation studies show it can install standard Windows startup entries. For example, an AttackIQ red-team exercise noted that Lumma setups used Registry Run keys to relaunch after reboot. This implies attackers may add Lumma to the HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run (or similar) to survive restarts.

On the evasion front, Lumma’s design minimizes traces. It often runs purely in memory (especially the stolen data collectors) and may wipe its own files after use. The heavy obfuscation already mentioned is a key stealth tactic. Lumma also encrypts all of its command-and-control interactions: its tier-1 domain list and Telegram/Steam fallback URLs are stored encrypted in the binary. When communicating, it does so over HTTPS through Cloudflare, hiding the true server IPs. The use of legitimate system programs (e.g. mshta.exe) as loaders also helps bypass behavioral detection. In summary, Lumma employs multiple anti-analysis layers (obfuscation, encryption, living-off-the-land) to slip past automated defenses.

Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) Ecosystem

Lumma thrives as a service. Researchers describe it as a turnkey infostealer platform: buyers purchase subscriptions and access a web panel to build tailored binaries and monitor stolen logs. The developer even created a brand: a distinctive bird logo and marketing materials (the slogan “making money with us is just as easy”). Affiliates can customize modules, choose which data to target, and add cloaking tools under each tier.

Third-party platforms play a role at every stage. Underground markets and Telegram channels are used to advertise and support the service. Darktrace noted Lumma’s official seller Telegram channel had 1,000+ subscribers by mid-2023. Underground forums are rife with ads for Lumma and even tutorial posts on using its ClickFix payload. After the takedown, cybercriminal forums reportedly offered “Lumma migration” discounts – deals to switch from Lumma to competing stealers like Raccoon, RedLine, etc. .

Lumma’s affiliates also leverage legitimate cloud services to bolster stealth. As noted, the C2 servers sit behind Cloudflare. The stealer can use Twitter/Tweet embeds or GitHub raw URLs to stage next stages. In one case, malicious web code on compromised sites fetched scripts from a Binance Smart Chain contract (so-called EtherHiding). Another campaign hosted its social-engineering landing pages on Microsoft or Google cloud domains. And the fake CAPTCHA pages themselves mimic Google’s reCAPTCHA interface to appear trustworthy.

Threat Landscape & Competitors

Lumma sits among a crowd of infostealer malware, but it has recently outpaced many older players. For years, tools like RedLine Stealer and Raccoon Stealer dominated the market. According to threat intel, Lumma surpassed them in prevalence by early 2025. Darktrace and others have documented Lumma infections occurring alongside other stealers – e.g. the same host showing C2 callbacks to Raccoon, Vidar, and RedLine infrastructure. This underscores that Lumma competes directly with these tools for cybercriminal use.

After Lumma’s takedown, competitors moved to fill the gap. Security reports noted sellers offering to help users “migrate” from Lumma to alternative stealers , and even reselling old Lumma logs on dark markets (at reduced prices). In fact, RedLine’s developers advertised special discounts to attract former Lumma affiliates. Analysts caution that shutting down one stealer often creates space for others: “when one goes down… someone else will pick up where Lumma left off”.

Nonetheless, Lumma’s impact has been uniquely large. Microsoft called it “the most widely distributed data-stealing malware family in the world”. It was linked to a huge volume of attacks: Microsoft said it disrupted campaigns that had hit millions of victims. Its compromises directly enabled real-world fraud: stolen credentials and payment info from Lumma were used for fraudulent bank transfers, shopping, and cryptocurrency theft. Even ransomware operators reportedly relied on Lumma logs. For example, a breach at Telefonica (attributed to the Hellcat ransomware group) was initially enabled by credential theft, possibly from an infostealer like Lumma.

The recent global takedown involved law enforcement from the U.S., Europe, Japan and private companies. Over 2,300 domains were seized, and dozens of “user panel” sites were taken down, cutting off Lumma’s command channels. This likely exposed hundreds of criminals. One write-up noted that de-anonymizing Lumma’s admin panels could reveal “hundreds of Lumma’s criminal users”. In the DOJ press release, the FBI highlighted disrupting “the most popular infostealer service available in online criminal markets” as a major achievement.

Mitigations

To protect against stealers like Lumma, security experts emphasize layered defenses. Multi-factor authentication can mitigate the damage of stolen passwords, and organizations should keep endpoints patched and running updated anti-malware software. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) tools can block malicious artifacts even if non-signature detections fail. User training is also critical: many Lumma infections began with tricking users into running a fake “update” or opening a luring email attachment. Monitoring for unusual login patterns or data exfiltration can help catch compromises early. In the long term, disrupting MaaS criminals like Lumma helps defenders stay ahead, but every organization must assume such tools will be repurposed or redeployed by other adversaries.