Explore WannaCry’s full campaign history, from its unprecedented global outbreak via the EternalBlue SMB exploit to its devastating impacts on industries. Learn how security experts contained the threat and why Xcitium’s analysis shines a light on every aspect of this notorious ransomware attack.

WannaCry remains one of the most infamous cyberattacks in history. In May 2017, this cryptoworm achieved global distribution within hours, encrypting user files and demanding Bitcoin payments on unpatched Windows systems. Its significance extended beyond the sheer scale of destruction—it delivered a sobering message to the cybersecurity world about the catastrophic consequences of leaked nation-state exploits targeting critical infrastructure.

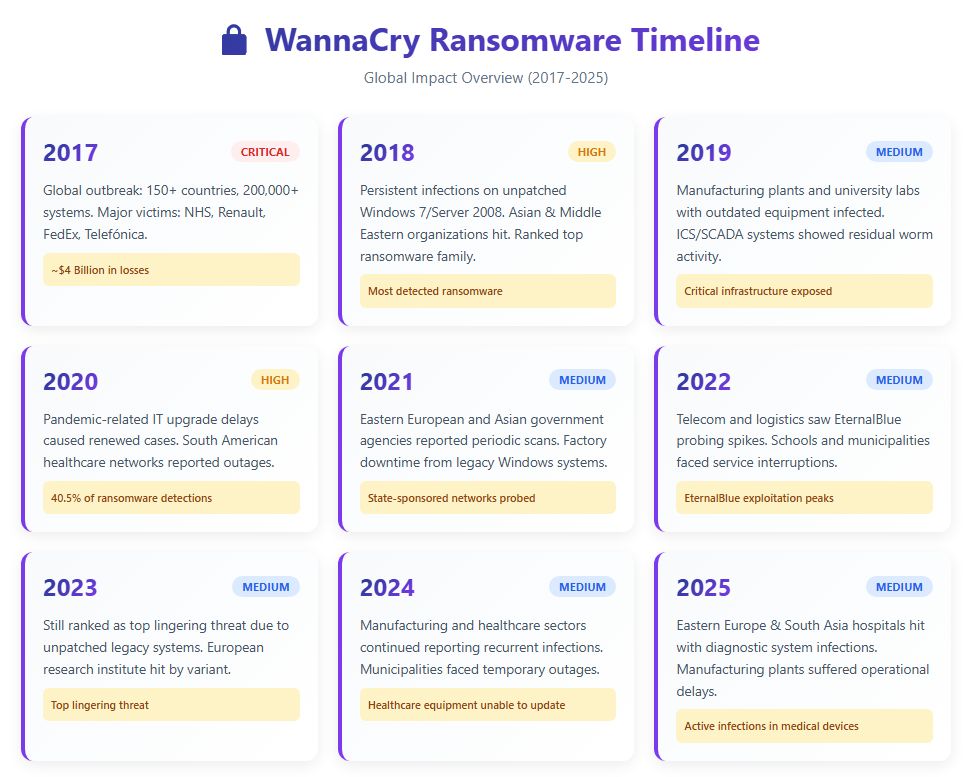

Even in 2025, WannaCry has not fully disappeared. Although the original outbreak was mitigated, the malware continues to resurface in environments that still rely on outdated or unpatched Windows machines. Security researchers consistently observe active variants, automated scanning attempts, and opportunistic attacks exploiting the same underlying vulnerabilities. This persistence underscores that WannaCry is not merely a historical event; it remains a real and ongoing threat for organizations that have not fully closed the gaps exposed eight years ago.

Global Spread via the EternalBlue SMB Exploit

The WannaCry ransomware spread quickly due to the EternalBlue (CVE-2017-0144) vulnerability in Microsoft’s SMB protocol, which had been initially exploited by the NSA but was leaked by the Shadow Brokers. Despite the patch, MS17-010, issued by Microsoft on March 2017, most systems were not patched. After the WannaCry attack on the 12th of May 2017, it started searching the Internet for systems with port 445 of the SMB protocol open and unpatched. According to observation, a Windows 7 machine scans about 25 random IP addresses each second, which used the EternalBlue exploit to propagate WannaCry.

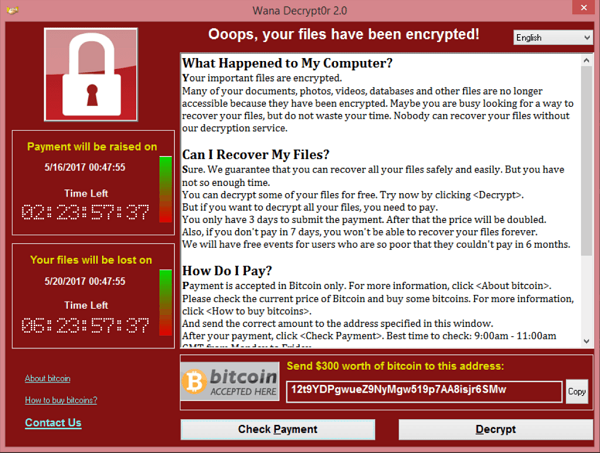

After successfully gaining entry into the computer, the ransomware extracted the encryption component, produced cryptographic keys, hid the working folder, and eliminated the shadow files. The ransomware also encrypted files belonging to users, appended “.WNCRY” to the files, and displayed a ransom demand of $300 sent via Bitcoin, which increased to $600 after three days, stating that the files shall not be accessible unless paid.

Unlike ransomware, which is normally disseminated by phishing mails, WannaCry malware largely used direct exploits on the target network. In an organizational setup, it propagated to other computers using SMB shares and also to external computers by randomly targeting their IPs. This resulted in potentially crippling an unpatched environment within minutes, rendering health, business, and organizational setups with connected computers incapable of accessing most computers within a morning. This resulted in operational downtime due to locked computers and ransom messages, proving the destructive nature of the global malware attack.

Significant Attacks and Costs

WannaCry has struck various institutions, including the following high-profile ones:

- UK National Health Service (NHS): Around 70,000 computers were affected, which led to the disablement of a third of the country’s hospitals, 19,000 canceled appointments, and £92 million losses.

- FedEx (USA) and Renault (France): The U.S. operations saw halted shipments because of the system lockout, and Renault halted factory production due to affected computers.

- Honda and Nissan (Japan/Global): Automobile manufacturers delayed operations due to affected workstations, which hindered operations in Japan and Europe, with Nissan stating it has been affected worldwide.

- Telefónica (Spain) and others: Thousands of computers were locked and shut down, while further disruptions were reported within other Spanish companies and segments of the Russian government’s computer systems (Interior Ministry, among others). Smaller companies, institutions of learning, and other entities were also affected.

- Global Reach: According to security analysts, more than 10,000 organizations and 150 countries were affected within a day, with the number of affected computers ranging into the low hundreds of thousands.

- Economic Impact: Industry experts subsequently calculated worldwide losses to amount to approximately $4 billion. In contrast, the attackers’ wallets were reported to hold $386,000, which translates to $2 per affected machine.

Rapid Security Response: Kill Switch and Containment

As WannaCry started spreading on May 12, cybersecurity professionals worked on containing it. A turning point came when it was revealed that WannaCry has a hidden ‘kill-switch’ by design. WannaCry tried to connect to a fixed domain (starting with ‘iuqerfsodp9’…). If it failed to connect, it started encrypting files, and if it did, it quit. Identifying the domain to be unregistered and registering it instantly halted the global WannaCry worm, which stopped working once it connected to the newly registered domain.

The appearance of the sinkhole greatly slowed the rate of new infections and gave precious time. Large technology companies soon blocked traffic associated with EternalBlue, and Microsoft issued patches on May 13 for unsupported versions such as Windows XP and Server 2003. Remediation tools such as WannaKey and Wanakiwi were developed to retrieve the encryption keys from the RAM of computers not rebooted after infection.

In contrast, the threat evolved. Variants were noted by May 14 to include ones with changed Kill Switch domains, such as ifferfsodp9…, and ones lacking the Kill Switch domain. These were able to continue encrypting files, regardless of the checks on the network. A botnet built using the Mirai code also targeted Hutchins’ sinkhole with a DDoS attack. Hence, a new web hosting service, which could support it, was required.

Nevertheless, with the fast patching and the kill switch, the outbreak could be controlled effectively within a couple of days. Infection levels dropped significantly by mid-May. An important issue is raised by this case, and it highlights the danger of vulnerable exposed SMB ports and unpatched Windows machines.

Variants and Copycat Ransomware Strains

- Although the 2017 WannaCry outbreak was controlled, it did not completely die out.

- Copycat versions came up in the following years.

- Just after the activation of the kill switch, new “rebooted” variants started to emerge.

- On the 14th of May, 2017, samples were discovered which altered and removed the sinkhole domain.

- These versions were also capable of infecting unpatched computers.

- There is also private VirusTotal data showing another variant lacking the kill-switch logic, which propagated silently on May 12-14.

- Indicators of WannaCry’s resurgence emerged after 2017.

- In August 2018, TSMC also contracted a WannaCry-like attack on 10,000

- This variant did not have a ransom note and merely rebooted computers.

- Analysis revealed it to belong to the WCry family.

- There has beenactivity even several years after.

- In 2021, Check Point saw a 53% increase in WannaCry detections.

- Detections were also found by leftover infections searching the web.

- Others came from newly assembled samples which were also based on the EternalBlue exploit.

- As long as unpatched Windows computers are connected to the Internet, WannaCry is able to wreak havoc

- Other ransomware attackers also adopted the WannaCry methods.

- NotPetya/ExPetr employed the EternalBlue exploit but behaved more like a

- Certain contemporary ransomware variants possess a “worm-like” dissemination ability.

- None have reached the scale of the original WannaCry attack.

- The fundamental take-home message is: An exploit found by NSA could act as a weapon used by attackers again and again.

Technical Analysis Summary

- Exploit & Propagation: WannaCry gains entry into respective systems by exploiting the ‘EternalBlue’ vulnerability found in Windows’ SMBv1. After entering a system, it scans both local and randomly selected IP’s on the internet (approx. 25 IPs each second) to look for other ports running SMB.

- Worm Behavior: The malware operates by residing on the Windows operating system as a service named “mssecsvc2.0.” When it successfully infects a computer, it creates several threads to initiate remote exploits on each target computer it discovers. Moreover, it searches the connected drives to encrypt files stored on external media drives.

- Kill-Switch Logic: The WannaCry malware, when it is started, tries to send an HTTP request to a fixed domain name (for example, iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com). If the domain is resolved, it

- File Encryption: The payload looks such files, such as documents, image files, databases, and generic files (DOC, PDFF, MP3, and so on), and encrypts each file using AES and RSA, adding “.WNCRY” to the files and writing a ransom note to demand 300 to 600 Bitcoins.

- System Disruption: WannaCry is using WMI commands, such as “vssadmin delete shadows,” to delete Volume Shadow Copy backups and disable System Restore (attack T1490). WannaCry sets up some payload files to be hidden, with full access permissions granted to “Everyone.” WannaCry also attempts to disable some services, such as the Exchange service, to lock data (attack T1489).

- Crypto & C2: WannaCry has used Tor for communication with the control server (activity T1090) and a bespoke encryption algorithm on top of it. Ransom payments are made to three Bitcoin accounts hardcoded into the malware, but only a small amount (around 50 BTC) has ever been paid.

In essence, WannaCry is a worm-SMB exploit and is also a file encrypting malware. In other words, it is extremely fast-acting to unpatched computer networks, utilizes a domain-based kill-switch, and also has robust cryptography capabilities.

MITRE ATT&CK Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs)

| Tactic | Technique | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Access (TA0001) | T1210 | Exploitation of Remote Services – Uses the EternalBlue SMB exploit (CVE-2017-0144) to infect machines. |

| Execution (TA0002) | T1543.003 | Command and Scripting Interpreter – Executes code by installing itself as a Windows service. |

| Persistence (TA0003) | — | Create or Modify System Process – Registers a persistent service named “mssecsvc2.0”. |

| Defense Evasion (TA0005) | T1564.001 | Hide Artifacts – Uses attrib +h and ACL modifications to hide files and grant access. |

| Discovery (TA0007) | T1018 / T1120 | Network Service Discovery – Scans local/remote hosts for SMB and enumerates attached drives. |

| Lateral Movement (TA0008) | T1570 | Lateral Tool Transfer – Attempts to copy itself over SMB shares to other systems. |

| Command & Control (TA0011) | T1090.003 | Encrypted Channel – Uses Tor proxy for C2 communication. |

| Impact (TA0040) | T1486 / T1489 / T1490 | Data Encrypted for Impact – Encrypts files, stops key services, and inhibits system recovery. |

Case Study: Xcitium vs. WannaCry Ransomware

WannaCry ranks among those cases that symbolize one of the most catastrophic outbreaks of ransomware malware. The resultant effect of this malware was that it disabled worldwide networks almost instantly. A vulnerability that was well-known was used to facilitate a quick and automated attack. This had adverse effects because several organizations had to go offline with losses resulting from unpatched systems being prone to ransomware attacks.

This current video showcases how Xcitium stops WannaCry ransomware right when execution occurs. Xcitium’s patented Zero-Dwell architecture ensures that no untrusted file gets a chance to touch the underlying system. The ransomware only runs inside this safe zone with no access to any important data. Not even when encryption occurs does any precious data get encrypted.

Within this demo, Xcitium is capable of isolating 46 WannaCry samples at a time. Despite this, no malware breaks out of containment. Encryption is not used. Lateral attacks are not triggered. Harm does not reach the endpoint.

Xcitium does away with dwell time, effectively neutralizes ransomware attacks instantly, and sustains business operations. This is a preventive measure and not a response.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

- Kill-switch Domains: The original sinkhole domain was

iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com. Variants used domains likeifferfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.comandiuqssfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com. Any DNS records or HTTP activity to these gibberish domains suggests WannaCry activity. - File Extensions & Names: Encrypted files have the extension

.WNCRY, and inside files often begin with the ASCII string “WANACRY!” in their header. Ransom notes (e.g.,How_To_Decrypt_My_Files.html) and decryptor executables may also appear. - Service Name: On infected Windows systems, look for a service called “mssecsvc2.0” (display name “Microsoft Security Center (2.0) Service”) that was not originally present.

- Bitcoin Wallets: Known Bitcoin addresses tied to WannaCry include:

- 13AM4VW2dhxYgXeQepoHkHSQuy6NgaEb94

- 12t9YDPgwueZ9NyMgw519p7AA8isjr6SMw

- 115p7UMMngoj1pMvkpHijcRdfJNXj6LrLn.

Any payments to these wallets are likely ransom payments for WannaCry.

- Network Indicators: Any inbound exploit attempts on TCP port 445 (SMB) carrying known WannaCry payload signatures should be flagged. Additionally, unauthorized Tor processes or traffic (T1090 C2) could indicate the ransomware’s use of encrypted channels.

- Process Activity: Observation of

wmic.exe,vssadmin.exe, orbcdedit.exeinvoked soon after SMB compromise can signal WannaCry deleting backups (T1490). File system activity that shows mass renaming of user files to.WNCRYis also a hallmark.

WannaCry Ransomware SHA-1 Samples & Zero‑Dwell Threat Intelligence Reports

Conclusion

A Global Lesson in How Fast Ransomware Can Break the World

The WannaCry outbreak remains one of the clearest warnings in cyber history: when a single vulnerability is left unpatched, the entire world can collapse in hours.

Using the EternalBlue exploit, WannaCry spread across 150+ countries, crippling hospitals, factories, couriers, and governments. Tens of thousands of systems were locked within minutes. Billions of dollars in damage followed.

All because unprotected machines were allowed to execute malicious code the moment it hit them.

Why This Threat Still Matters Today

WannaCry didn’t disappear it evolved. Variants, copycats, and EternalBlue-based malware continue targeting unpatched systems years later. And the root problem persists:

- Endpoints still execute unknown files

- Legacy machines remain unpatched

- SMB ports stay exposed

- Organizations rely on detection after execution

- Wormable exploits propagate faster than humans can respond

The world learned how quickly a global ransomware worm can take down healthcare, logistics, and critical infrastructure.

Any environment that allows unknown code to run is still vulnerable.

Where Xcitium Stops WannaCry Instantly

Organizations protected by Xcitium Advanced EDR, powered by the patented Zero-Dwell Platform, experience the exact opposite outcome.

- Unknown files are isolated the moment they execute

- Wormable ransomware cannot encrypt or spread

- EternalBlue-driven payloads run only in a safe, virtual environment

- Lateral movement attempts are cut off instantly

- Even dozens of WannaCry samples cannot touch real data

Xcitium eliminates dwell time entirely shutting down WannaCry and all variants before they interact with the system, before encryption begins, and before the first workstation is lost.

This is not response. This is prevention.

Protect Your Business From the Next WannaCry

WannaCry showed the world what happens when attackers move faster than defenders.

Xcitium ensures they never get that chance again.

Keep your endpoints, operations, and infrastructure safe from wormable ransomware. Choose Xcitium Advanced EDR.